We cannot define what a “Good User Story” is… And it does not matter

Why the product backlog?

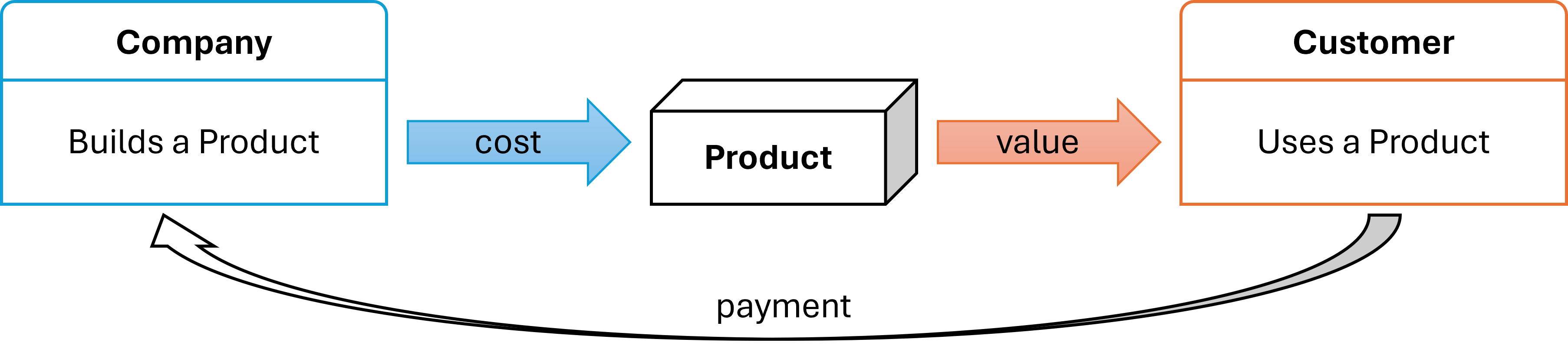

Product: cost and value in a backlog

To define the product backlog, I would like to introduce a quite simple definition of a product. A product is anything that a company can make, to bring value to some customer and get payment for it. Of course there can be many variations, the user may or may not be the customer, the payment may or may not be from the user; but this is enough to reason about the product itself, its cost for the company and value for the customer.

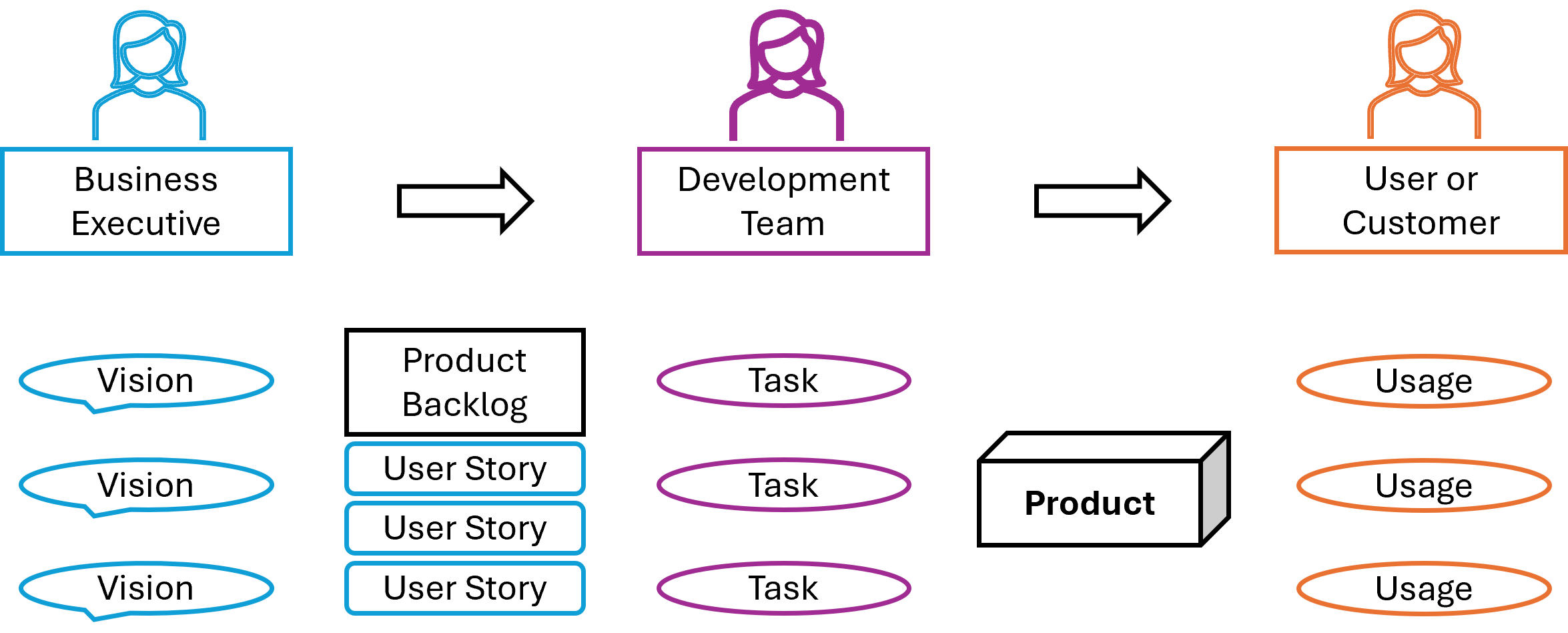

The essential element that is lacking in this description is time. The product cannot be built instantly, there must be a process where it is somehow “sliced” in many distinct parts, which are then implemented.

Not everything must be Agile

In the previous schema, I did not assume that the product management was Agile. We can very well define a waterfall process, where:

- The purpose of the product is defined by the executives, business analysts, or even the client

- The expected user experience is completely defined and documented

- Every step of the implementation is planned

- Only then the development starts

- And the product is released when finished

Here the purpose of product backlog items is to:

- Define all tasks for the development team

- Estimate their complexity or development time or budget

- Plan according to dependencies between items

- Ensure that the sum of items will make the expected product

- Monitor anytime that the project is on track

This process is very much not Agile, but we can see that the product backlog items could still be called user stories if they were written from the point of view of the increment in value for the customer. To be abundantly clear, we can write “as a … I want to … so that …”, we can call it a user story, and yet not be Agile at all. Agile is defined by principles not techniques.

In the rest of this article, we consider user stories in Agile methodology context only.

The “Agile User Story”

Individuals, interactions, and customer collaboration

Agile or not, we have seen that one essential purpose of a user story is to represent some slice of the product that can be implemented by the development team. What remains to be defined is what information we want on this “slice description”, how it is created, how it is used.

One essential characteristic of an Agile user story is that it should allow interactions between the development team, the product team, and the customer. Since we are not using a waterfall methodology we don’t have to make a complete user story, and really, we must not make a complete user story with every implementation detail. We would lose all the benefits of the Agile approach.

- We want the customer to discuss the user story, this is the best way to ensure that all slices increase the value, from the customer perspective

- We want the development team to discuss the user story, so that they can clearly understand the purpose and produce the best technical solutions to achieve it.

It means that a story is not some static piece of information, but is both the result of interactions, and the medium to encourage interactions. It is the product owner's job to make these stories come to life and help them grow through collaboration.

Priorities and roadmaps, or responding to change

I have often read that one essential purpose of a user story is to give an estimate for the development team work, so that we can make roadmaps and plan.

The essence of the release planning meeting is for the development team to estimate each user story in terms of ideal programming weeks

We want roadmaps, we want to know when things will be done, we want to prepare the next steps. Of course, the marketing team want to know the release date to promote the next version or the product. Of course, business analysts want to know when we are going to get a return on our investment.

At the same time, we want to be able to respond to changes, we want to be able to update the product backlog with new priorities, we want to react to any customer feedback we have received.

It seems contradictory. Because it is. The usual workarounds are:

- Hierarchical roadmaps: more details and more confidence for the short term

- Temporary roadmaps: they must be constantly updated to respond to changes

- Absence of commitment: there should be a disclaimer about what is, and is not, a commitment

This is another difference between product ownership and project management. The path cannot be known in advance, the roadmap will evolve, and it is again the product owner’s job to maintain the set of all user stories, the product backlog.

So many frameworks

INVEST principles

The acronym INVEST was coined by Bill Wake to determine what is a good user story and what is not is still widely referenced.

But what are characteristics of a good story? The acronym “INVEST” can remind you that good stories are:

I — Independent

N — Negotiable

V — Valuable

E — Estimable

S — Small

T — Testable

Independence means that each user story could be implemented independently. Of course, this is not always possible, but when it is, it is a good quality to have.

A negotiable user story is a user story where details are not yet defined and are meant to be the result of discussions between the development team and the customer. Of course, many notes can be added to the story when new information has been uncovered.

A story must be valuable. This is the most important characteristic of a user story. It must be a slice of the product that increases the value (from the customer's point of view, as always). It is really the reason for the user story to exist in the first place.

A story should be estimable, meaning that we should be able to guess how long the story will take to implement. This contradicts the negotiation, if we don’t know what and how we are going to implement, we can’t predict how much time it will take.

A note of caution: Estimability is the most-abused aspect of INVEST

A story should be small. This relates to the estimable characteristic, but only as a cutoff, a story is either too big or small enough to be handled efficiently.

And finally a user story should be testable. The first point is to avoid technical debt with unit, integration, and regression tests. It also means that we can define functional and user experience tests. We must be able to decide very clearly if the value of the user story has been added or not. Being well defined and testable are often related.

Many frameworks, many complains

Frameworks in general can be very good tools:

- They can guide us when we don’t know where to start

- They can be ubiquitous enough to ease communication with shared patterns

- They can guarantee no part of the process is missed, every step is documented

- They can guarantee consistency in our work, always using the same pattern

- They can improve efficiency, not having to reinvent the wheel

So why are there so many competing frameworks if they are supposed to give the whole solution? For example, there are at least 9 well known, and widely used, prioritization frameworks (productcompass.pm). They all seem very reasonable; they all are common sense. None is perfect otherwise the other ones would have been forgotten. None is good enough, otherwise we would have stopped trying to make a better one. There are concerns and complaints with all of them.

Similarly, there are no obvious ways to follow the INVEST principles. For example, what should we do with a “not-small-enough” user story? I have seen many variations of:

- We can try and make it smaller by removing anything that does not bring value

- We should split in smaller user stories

- We should consider the user story to be an epic containing user stories

- We should organize user stories by epics and themes

All these ideas make sense. But all of them somehow contradict the independence characteristic. If we plan a full epic instead of picking the high priority user stories only, is it OK? If we need the infrastructure before deploying one feature, is there really a way around that? Is it worth trying to phrase it differently just because one framework says so?

The product backlog, by nature, cannot be homogeneous. That’s OK, we must learn to live with that, it only means that the product owner must maintain it. Any choice we make is a compromise.

Can we be Agile?

Following a framework is not a purpose

Applying frameworks blindly is extremely dangerous. They are tools, they are techniques, and they are useful only when we remind ourselves why we use them in the first place.

I have the same opinion in software engineering, where there are many frameworks and libraries. Frameworks are usually end-to-end solutions for a given problem, for example a web framework will handle the HTTP server, the REST API endpoints, the database connections, … We only have to add some views to define the content and plug-in our database. On the other end libraries only provide tools for specific tasks; there are databases connection libraries, API design libraries, … We still must make them work together, and we control each part we use.

The main danger of frameworks is that sometimes they lead us to change many different parts of the process, just because we want one part to fit in the framework. This can sometimes be very insidious, and we must be very careful not to obey frameworks blindly. We should not adapt our process to frameworks, instead we should use them as tools, not get attached to them, so that we can change whenever it makes sense; so that we can keep control of our objectives.

We must remind ourselves of why we wanted user stories.

We want different things

Continuous discovery — The product backlog is the result of the continuous discovery process, in which the opportunities to increase value are investigated. The resulting user stories must capture what should be added to the product, from an external point of view (from the user point of view). These user stories are not set in stone, they are meant to engage the discussion, with the customer, with the development team, with the designer.

Prioritization — User stories are meant to help prioritize the work to be done. They are the elementary building blocks of the product, and they must be prioritized. As we discussed, there are many ways to do that, but in the end, there must be some kind of user story map, where we can draw a line separating the selected user stories for the next release. It is enough to only compare user stories to each other, to define priorities and complexities.

Continuous delivery — User stories are meant to guide the development team on what to build. They should give a clear explanation of why we want to build something, the expected user experience, and the value it brings to the customer must be truly clear for the development team. Only when they have all these answers, can they choose the best technical solution to build the user story in the product, effectively increasing the value of the product.

When we realize that we manipulate user stories with many different purposes, it becomes obvious that we cannot create “the one perfect way to write them”, because the best way depends on what we expect to do with it. It is OK to have different views on the same user stories. Moreover, they are meant to evolve. In the discovery stage, whatever hypothesis is tested must have the information needed to test its value, nothing more, nothing less. In the delivery stage, any information asked by the team must have an answer, even details that were not needed to prioritize the story.

Instead of trying to build the perfect product backlog with perfect user stories, I think we should acknowledge that there are different purposes for the backlog; different views where the information presented is not the same.

We need product management

I did not give a definition of a “Good User Story”, and well… My whole point is to argue that it does not matter. So, what should we do? Can we forget user stories altogether? Of course this is not what I mean.

User stories are very useful when they allow interactions between teams, when they allow the definition of an MVP to test an idea, when they allow to prioritize the next sprint or next release, when they encourage developers to ask questions to the customers. No framework is ever going to guarantee this, it is the hard job of the product owner to do so. I would be particularly cautious with all “meta frameworks” where we can organize user stories in categories (technical, functional, …) and scope (epics, theme, …), we can quickly be lost in technicalities that do not help discovery nor delivery.

We should use all the tools we have, only to the extent that we can verify they help us with the outcome. The quality of a user story has very little to do with what is written on the card, its success can only be measured by the interactions and collaborations it created.